California Fire News

California Fire News |

| Helicopter aviators weigh nighttime water drops - News for Inland Southern California Posted: 27 May 2007 08:38 PM CDT See story at: Helicopter aviators weigh nighttime water drops " From Griffith Park to Catalina Island, helicopter pilots periodically battle wildfires at night in Los Angeles County, and now at least two agencies are considering bringing night water drops to the Inland area. "We've been working on it for the last year or two," Chief Mike Padilla said of Cal Fire's study of how night water drops might be made by his statewide helicopter fleet. "LA. County (Fire Department is) probably the most experienced agency in night firefighting. "We're talking to them ... and assessing what we want to do." Story continues below  Greg Vojtko / The Press-Enterprise An inmate fire crew practices exiting a helicopter at Prado Helitack Base in Chino. The Inland area is considering nighttime water drops, which must be made from a lower altitude, raising the risk of collisions with power lines and other helicopters. Preliminary evaluations may be made with one or two of Cal Fire's 11 Vietnam War-era military-surplus helicopters, including one stationed in Hemet. But a full-scale program would require newer and specially equipped choppers, which are at least three or four years away, Padilla said. Cal Fire is responsible for fire protection on state lands and it serves as Riverside County's fire department. In San Bernardino County, the sheriff's 15 helicopter pilots and their supervisors have been discussing the possibility of making nighttime water drops. Every fire season, one of the sheriff's 11 helicopters is assigned full-time to daylight firefighting duty under a contract with Cal Fire. "We have the ... ships, the night-vision goggles, the (water) buckets and pilots," Lt. Tom Hornsby said. "So from the policy decision to do it, it would take us two months (to develop guidelines and to train an initial group of pilots). But that would be hard-charging. And then we'd have only three or four pilots to drop water at night on goggles." Nine additional months would be required to train the remaining pilots, he estimated. But Hornsby emphasized that no policy decision has been made for sheriff's pilots to do nighttime firefighting. That decision -- for the Sheriff's Department, Cal Fire and any other agencies that might consider night drops -- depends partly on whether the benefits are worth the risk to pilots, who would be flying low over turbulent fires, surrounded by wires and other obstructions, in the dark, officials agreed. Benefit vs. Risk "The benefit of (night water drops) is: Fire isn't as intense at night so you can get a greater effect from your water dropping," said Chief Bill Smith of the Running Springs Fire Department in the San Bernardino Mountains. But even at night, water drops must be made from low altitude, which raises the specter of collisions with everything from power lines to other helicopters. In July 1977, two water-dropping helicopters -- whose pilots were using night-vision goggles -- collided while preparing to land at a reloading point in the Angeles National Forest. One pilot was killed. Another was critically injured. "That pretty much put a damper on any night flying," recalled Smith, a U.S. Forest Service retiree. The Forest Service, which operated one of those helicopters, no longer conducts night water drops and has no plans to resume them, said spokeswoman Rose Davis. The other helicopter was operated by LA County Fire Department, whose crews didn't return to using night-vision goggles until 2001 -- and then primarily for nighttime rescue missions. "It took us from 2001 to 2005 flying goggles in our area until we felt comfortable doing night firefighting," recalled Tom Short, senior pilot for LA County Fire Department. "We did not just jump into this." Story continues below  Night goggles amplify existing light, everything from starlight to streetlights. Pilots say they use the goggles on nearly every night firefighting flight, though not necessarily during the water drop. "I'll flip the goggles up because I have enough light around the fire to see," Short said. "It's when I'm going to and from my water source that I'll use the goggles." Ponds, lakes and other water sources often are in unlighted locations and close to wires that are difficult, sometimes impossible, to see from the air even during the day, requiring pilots to search for the poles or towers that support the lines. So it's important for pilots to be familiar with an area in daylight before they attempt night drops there, Short said. For that reason, he says it's especially reasonable for Cal Fire to proceed slowly. "I think it's a very wise thing (for Cal Fire) to be wary ... because of the large area in which their pilots respond. It's impossible to have (detailed) knowledge of the whole state," said Short, who had flown in Los Angeles County for about 10 years before he attempted water drops there with night-vision goggles. Now, 30 years after the first goggle-related collision of two firefighting helicopters, Short and others say the collision is worth remembering as an indication of the potential and the risks of night firefighting. "The technology of those goggles was nothing like we have now," he emphasized. "But that accident sticks in our minds." Military Leads Way As Cal Fire and the San Bernardino County Sheriff's Department each consider nighttime water drops, their pilots with military flight experience tend to be the most comfortable with the idea. "I've got 300 or 400 hours in night-vision goggles ... with the military," said Padilla, Cal Fire's top-ranking aviation official. "The last time I flew them was in Bosnia in '99." One of his staff officers wore goggles when he was in the Marine Corps and flew Marine One, the president's helicopter. At the sheriff's helicopter unit, three former military pilots have become the agency's night-vision goggle instructors. Beginning last year, the San Bernardino County sheriff's pilots have been using the goggles to fly at night on their police patrols. And six of their newest helicopters are capable of making night water drops. Because it takes time to become comfortable using the goggles during all conditions, each pilot uses the goggles on flights over urban areas before progressing to more difficult geographical areas. Remote portions of the desert are particularly dark. And in dark mountainous areas, the terrain creates additional hazards. "We may add (rescue) hoist operations as the next mission," said Hornsby, the unit's lieutenant. "And after that, firefighting, or maybe not." A key consideration before risking pilots and spending perhaps $100,000 on equipment and training, Hornsby said, is determining how often night water drops would be needed. That question remains unanswered, he said. "We're not there yet." Reach Richard Brooks at 909-806-3057 or rbrooks@PE.com " |

| CA-MMU- Hwy 120 & Tulloch Rd. Vegetation Fire Posted: 27 May 2007 03:17 PM CDT Hwy 120 & Tulloch Rd. Vegetation Fire Thursday, May 24, 2007 - 11:25 AM Bill Johnson MML News Director San Andreas, CA -- According to CAL FIRE officials and the Highway Patrol, there is a vegetation fire on Hwy 120 at Tulloch Rd. The fire was caused by a trailer that disengaged from a vehicle. CAL FIRE crews have been dispatched from stations as well as the Columbia Air Attack Base. CHP officers are also enroute to that location. According to crews on site, the fire is covering between three to five acres on the south side of the highway." |

| Red Flag Warning For Eastern Lassen Co.(5/27/07) Posted: 27 May 2007 01:37 PM CDT Red Flag Warning For Eastern Lassen Co: RED FLAG WARNING NATIONAL WEATHER SERVICE RENO NV 620 AM PDT SUN MAY 27 2007 CAZ278-NVZ450-453-458-272300- /O.NEW.KREV.FW.W.0001.070527T1800Z-070528T0300Z/ EASTERN LASSEN COUNTY-WESTERN NEVADA SIERRA FRONT- WEST CENTRAL NEVADA BASIN AND RANGE-NORTHERN WASHOE COUNTY- 620 AM PDT SUN MAY 27 2007 ...RED FLAG WARNING IN EFFECT FROM 11 AM THIS MORNING TO 8 PM PDT THIS EVENING FOR WIND GUSTS NEAR 30 MPH AND HUMIDITY BELOW 15 PERCENT.. THE NATIONAL WEATHER SERVICE IN RENO HAS ISSUED A RED FLAG WARNING...WHICH IS IN EFFECT FROM 11 AM THIS MORNING TO 8 PM PDT THIS EVENING. ...THIS RED FLAG WARNING EFFECTS THE FOLLOWING AREAS.. IN NORTHEASTERN CALIFORNIA FIRE ZONE 278. ..EASTERN LASSEN COUNTY SOUTH OF SUSANVILLE IN WESTERN NEVADA FIRE ZONE 458. ..NORTHERN WASHOE COUNTY SOUTH OF GERLACH FIRE ZONE 450. ..THE RENO, CARSON CITY, MINDEN AREA FIRE ZONE 453. ..PERSHING, CHURCHILL AND NORTHERN LYON COUNTIES WEST OF HIGHWAY 95 LOW PRESSURE WILL MOVE INTO THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST TODAY AND PUSH A FRONT ACROSS NORTHERN NEVADA. AHEAD OF THE FRONT...WINDS IN THE WILL INCREASE LATE THIS MORNING WITH GUSTS NEAR 30 MPH MOST OF THIS AFTERNOON AND EVENING. DRY AIR AHEAD OF THE FRONT PRODUCED POOR HUMIDITY RECOVERY THIS MORNING AND WILL ALLOW HUMIDITY TO DROP BELOW 15 PERCENT THIS AFTERNOON. A RED FLAG WARNING MEANS THAT CRITICAL FIRE WEATHER CONDITIONS WILL OCCUR. IF YOU HAVE OUTDOOR PLANS TODAY USE CAUTION NEAR DRY FUELS. |

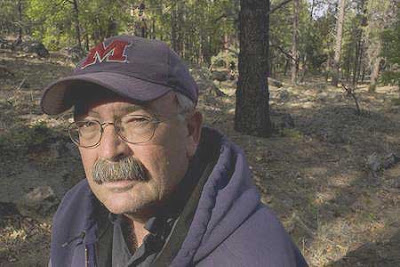

| Why firefighter set forests ablaze remains unclear Posted: 27 May 2007 12:14 PM CDT  Editor- This is a great must read story... Editor- This is a great must read story...Why firefighter set forests ablaze remains unclear:

Dennis Wagner The Arizona Republic May. 27, 2007 12:00 AM On June 23, 2004, a 55-year-old man stopped his pickup truck along a dirt road near a mud bog nestled in Ponderosa pines 45 miles south of Flagstaff. It was not unusual for Van Bateman, fire management officer for the Mogollon Ranger District, to be out in the woods, especially during wildfire season. But on this date, the U.S. Forest Service boss did something peculiar: After hiking down a short trail, he picked up a handful of dry pine needles, ignited them and placed them next to a dead oak tree.""It smoldered," Bateman later told investigators. "I just thought after I lit it, I thought, 'Hell, we'll just have a lightning fire here today for the boys to do something.' I knew the fire was going to grow and not go out." That statement, and the act it describes, ended the career of a federal employee who spent more than three decades protecting the West's wild lands. It also bewildered friends and colleagues who knew Bateman as a conscientious firefighter. In fact, he had become a near legend in the world of smoke jumpers and disaster-planning experts. The Federal Emergency Management Agency honored Bateman as one of 13 "everyday heroes" for his Sept. 11 emergency management in New York after terrorists attacked the World Trade Center. A year later, he oversaw elite teams battling the 469,000-acre Rodeo-Chediski Fire, Arizona's largest known blaze. For a man who began beating down flames and saving lives at age 20, the role of firebug seemed unthinkable. Yet the fire at the Boondock Tank bog was not an isolated incident. Bateman also confessed to setting the nearby Mother Fire six weeks earlier. And investigative records indicate he was suspected of starting other blazes. Why? That is the question asked by friends, family and hundreds of colleagues who risked their lives beside him on the fire line. Why would an expert on the lethal devastation of wildfires suddenly begin setting them after 34 years of public service? Why would a guy with no criminal record, mental health history or financial motive try to burn down the Coconino National Forest? Bateman remained mute on those questions for three years. He let attorneys argue legal technicalities until he lodged a guilty plea in October. A few weeks ago, with a federal court sentencing set next month, Bateman returned to the crime scene with an Arizona Republic reporter to explain his conduct. "I'm not lily-white on this," he said, pointing to remnants of the Mother Fire, which burned a pile of debris in an area the size of a small patio. "I'm saying I came out here, and I was doing my job. I came out, and I lit this thing. Did I obtain the proper authorizations? No, I did not . . . (But) I wasn't trying to start an arson fire. I was just trying to clean this piece of country up. . . . I would be shocked if there's anybody who's spent their career in forest management who hasn't done this." Assistant U.S. Attorney Kimberly Hare, the federal prosecutor, points out that Bateman raced away from the fire scenes after igniting the blazes during peak fire season. "Anyone who sets a wildfire and leaves it unattended is committing what I think is a criminal action," Hare said. "There are reasons why there's a prescribed policy for doing a controlled burn." Bateman, now 57, pulled out a map and showed how, in his view, the Mother Fire could not have spread out of control. He said it was a humid day with no wind. He said he merely used flame to eliminate logs and debris. "I just helped Mother Nature along," he said. "Did this fire pose any threat? No." An hour later, touring a ravine where the Boondock Fire burned 21 1/2 acres, Bateman again said his only motive was "fuels reduction," a term for using fire to purge an area of deadfall and underbrush. Planned fires are a part of sound forest management. In fact, weeks after the Mother Fire, Bateman received an award from the Department of Agriculture for his use of prescribed burns to cleanse these same woods. In those instances, however, he filed the required paperwork. Bateman admits violating protocols with the Mother and Boondock fires. But he insists that forest supervisors frequently come across areas that "need a little fire put on them" and handle the problem instantly. "I burned 'em," he said. "That's all there was to it. I did not go through the proper steps." Joe Walsh, a U.S. Forest Service spokesman in Washington, D.C., declined comment on the criminal case but said his agency "does not condone any actions of our Forest Service employees that are contrary to law, regulation and standing policy governing prescribed burns." In Arizona, Mogollon Rim District Ranger Mindee Roth said she is not aware of employees igniting the woods without approval. "That's highly unusual," Roth said. "Things have changed. That's not appropriate in this day and age." Unanswered questionsWhen Bateman pleaded guilty last fall, then-U.S. Attorney Paul Charlton said the Forest Service officer had joined "a small universe of firefighters who, for reasons we may never fully understand, violated the public's trust by igniting fires, not extinguishing them."Several wildfire experts interviewed for this story said that they believe Bateman's account and that it seems to explain his conduct, if not justify it. Still, the explanation leaves unanswered questions: • Why did he lie to Department of Agriculture investigators when they first confronted him about the fires, denying responsibility? Why did he sign a statement, written by investigators, that says, "I have not started any fires that were not prescribed, authorized or controlled burns on Forest Service land"? Why did he confess only after being told that GPS tracking records and tire prints placed him at the scene of each blaze? Bateman says he thought the interrogation was part of an administrative procedure and he was trying to dodge disciplinary action. • Why did Bateman not claim even once in a four-hour interview with investigators that he set the blazes for fire management purposes? Bateman says investigators told him not to answer their questions with fire science terminology because they wouldn't understand, so he didn't explain his motive to clean the forest. • Why did Bateman say a fine line divides a firefighter and an arsonist? Bateman says the written line was based on a response he gave to an investigator who observed there are similarities between cops and criminals. "I have a large mouth," he said. "They can spin this any way they want." • Why did Bateman sign a plea deal? Bateman says he set timber afire without authorization, so he is guilty of that offense. If he went to trial and lost, he might face up to five years behind bars. Under terms of the plea agreement, arson charges (malicious fire-setting) were eliminated along with two other counts. He hopes to get probation rather than prison time. Bending the rulesBateman's supporters - and there are many among firefighters - focus on another question:Is it possible a man with so much training and experience would twice attempt to incinerate forests, failing both times? Their answer: No, it defies belief. "If Van wanted to do arson, he could have burnt down Flagstaff," said Larry Humphrey, a retired wildfire supervisor for the Bureau of Land Management in Safford. "He knows the topography, the conditions and the fuels. . . . There's nobody who knows fire, from beginning to end, better than Van does." Humphrey, who shared incident command duties with Bateman on the Rodeo-Chediski blaze, described his friend as "the best fireman I've ever seen in my career," a master of using prescribed burns to protect forests and human populations. "If I was in a tight spot, he's the person I'd want to watch my back." Humphrey said unsanctioned blazes are set all the time by Forest Service supervisors who want to reduce fuels without filing 30 pages of paperwork. "That's a damned minor infraction," he said. "There's not a fire management officer who didn't do that sort of thing. . . . If you had to bend the rules a little, you bent the rules. "There are so many people who think the Forest Service screwed him," Humphrey said. "My take on it is that Van got too famous. The Forest Service does not like any lower-level employees to get any kind of fame." Charlie Denton, a 43-year Forest Service employee who retired as fire operations officer for Arizona and New Mexico, scoffed at the notion of Bateman as a felon. "I have never met anybody who thought Van would do anything of a criminal nature," said Denton, now a forestry consultant at Northern Arizona University. Jim Paxon, a retired Forest Service supervisor who now works for Channel 12 (KPNX), said Bateman's fire-setting is not unusual: "I was in the Forest Service 34 years. I've done exactly that. I can't tell you how many times." Paxon said Bateman was known as a risk-taker and expert in using prescribed burns and backfires to prevent or defeat deadly blazes. He described Bateman as dedicated, gregarious, friendly - hardly the stereotypical arsonist. "This was just very strange," he said. "There almost appears to be a vendetta. Somebody had it in for Van." Losing a careerBateman is a mountain of a man with the rugged features of actor Wilford Brimley and a grandfatherly gruffness to match.He started working on a Flagstaff hotshot crew at 21 and wound up with a lifelong career. "Hell, I liked it," he recalled. "And I just stayed with it through a hell of a lot of work and just worked my way up through the organization." Coconino National Forest, always Bateman's base, provided plenty of opportunities to combat fire by leading the nation in lightning- and human-caused blazes. So he gained experience and ascended from grunt to crew leader to forestry technician to forest management officer. He was schooled in fire behavior analysis. By 1996, Bateman was a Type 2 incident commander, overseeing major wildfire operations throughout the West. In 2000, he was named a Type 1 commander, responsible for managing hundreds of emergency workers at the largest fires and national catastrophes. On Sept. 11, 2001, Bateman and his team were working a fire in Montana when they received instructions to head for New York, where terrorists had toppled the World Trade Center. Their aircraft, with a fighter-jet escort, was among only a handful in the U.S. skies on Sept. 12. New York officials relied on Bateman to plan day-to-day logistics for rescue operations. Bateman was invited back later to teach incident command practices. When Hurricane Katrina struck, Bateman was brought to New Orleans as a liaison. That was in August 2005, more than a year after Bateman lit the Mother and Boondock fires near Flagstaff. According to court records, an arson investigator with the Forest Service suspected Bateman even before the fires were set in mid-2004, which is why a tracking device was installed on his truck. What remains a mystery is why the government allowed a suspected arsonist to continue work in a vital position for at least 16 months before investigators finally confronted him. One possible explanation: Authorities were confused because a second fire-setter also had been working the area. In January 2006, two months after Bateman's indictment, Jesse N. Perkins of nearby Happy Jack was arrested by a Forest Service law enforcement officer. According to federal court records, Perkins was a meth addict, artifact looter and "self-proclaimed pyro" who admitted setting numerous wilderness fires over the years. He pleaded guilty and was sentenced last May to six months in prison. Bateman speculates that investigators thought he was responsible for fires set by Perkins and targeted him for prosecution because of the number and danger of those blazes. He says he will never understand why federal agents charged him criminally or why none of his bosses spoke with him about the allegations. Rules were broken and lies told, he admits, but everyone knew unauthorized blazes were set to avoid the red tape. Bateman says he loses sleep worrying about a prison sentence but has managed to stay busy while the justice system grinds. For the past few weeks, he has been helping a private landowner develop plans for a prescribed burn. "I gave the outfit everything," Bateman said, referring to the Forest Service. "I felt that after 34 years, if nothing else, the very least they owed me was to set me down and talk to me. And the fact that they wouldn't even do that, I thought, was pretty chicken. . . . It took 34 years of hard work to get a reputation as a good firefighter . . . and that went down the tubes." |

| You are subscribed to email updates from California Fire News - Structure, Wildland, EMS To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email Delivery powered by FeedBurner |

| Inbox too full? | |

| If you prefer to unsubscribe via postal mail, write to: California Fire News - Structure, Wildland, EMS, c/o FeedBurner, 549 W Randolph, Chicago IL USA 60661 | |